In April, I’m headed to Ireland on a family vacation. Where should I go? How should I prepare?

I’m availing myself of gamification. This Sporcle quiz is good for learning the 32 counties: Can you name the counties of Ireland? Apparently everybody always forgets about poor old County Longford.

Audible is helping me with my James Joyce classics: Dubliners and Ulysses. I’m not surprised, but it’s still cool to see the various Google Maps-based resources for following Leopold Bloom around Dublin, especially Walking Ulysses from Boston College.

Anybody want to recommend a good book on Irish history?

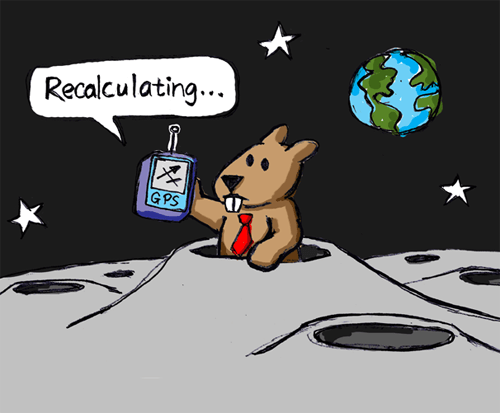

We’re renting a car, so I’m facing the prospect of shifting with my left hand, sitting on the right, driving on the left. Preparatory to this, I’m using Google Earth and Google Maps to get a feel for the roads I’ll be on. I’m told that the roads are so narrow that most of the time it hardly matters, but to me this seems worse, since you’ll come up on someone and have to remember by to veer quickly to the left, not right. So that should be fun. It would be nice to use the iPhone to help with maps, but I’m not sure if using the international data roaming is worthwhile. Are there temporary plans that make it worth doing?

I should point out that, although I sound completely clueless, I am already relying on the best possible travel resource. My wife researches and plans the trip, and I say “Where are we going today?”