When you record something on television to watch it later, you’re time shifting. That’s the fancy term for what might be called “latering.” I can’t watch this now. Let me watch it later.

Time shifting was a big deal when the first video recorders were introduced. It seemed almost magical at the time, since video content flowed like a river, never to return. Since then, technology has opened up many more possibilities.

These scenarios have the same basic time or place-shifting premise in common.

- I’m at Starbucks and I hear some music that I’d like to play for my wife at home.

- I’m checking Twitter on my iPhone and I see a reference to a New York Times article that I don’t want to read on my tiny screen.

- My brother recommends a book that I want to check out next time I’m at the library.

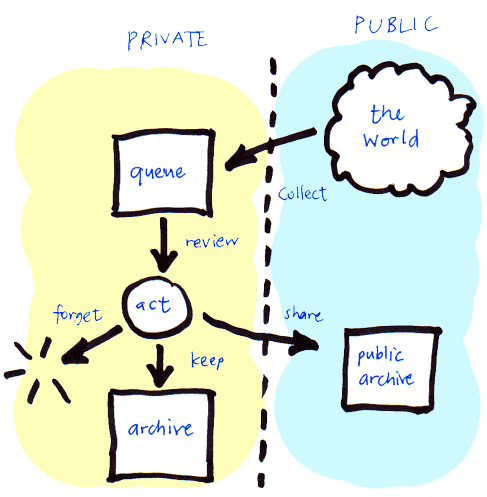

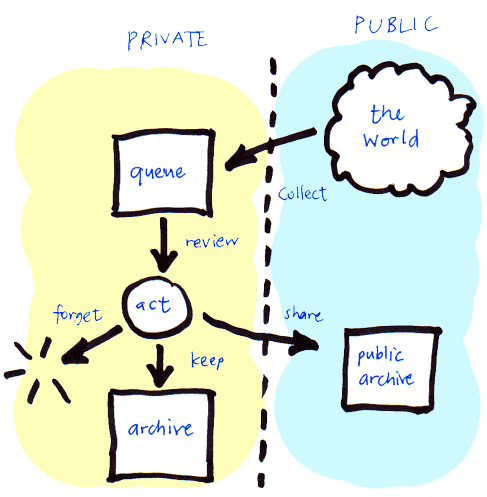

All of us have evolved tools for dealing with scenarios like these, from pen-and-paper lists to spreadsheets and specialized web services. I manage a bunch of these lists with a variety of tools. I keep books that I want to read on an Amazon Wish List, but books that I’ve read get added to my archive on LibraryThing. I use Shazam to identify music and then I listen to it with Rhapsody. I use iTunes to keep track of podcasts, but getting the podcasts into iTunes can be tricky. Individually these systems are powerful and convenient, but taken together they can befuddle. It was Instapaper that made me realize the value of something more universal. Instapaper lets you mark any URL with the magic words “read it later”. It then gets added to a queue that you look at later. That’s simple enough. The cool part is that so many other applications have added an Instapaper “read it later” hook. So I can route things to Instapaper from any device, any application (almost).

One of the nice things about Instapaper is that it’s platform agnostic. It’s not trying to keep you in its own ecosystem, the way Apple or Google might. Here’s an example of what I mean. While at my work computer, I happen across a YouTube video, and I want to tag it for watching on my AppleTV at home. But Apple has no interest in playing nicely with Google, so they make it painful to watch YouTube videos. Wouldn’t you rather watch one of *our* videos instead?

I want a universal “later” button that lets me add any resource to a single feed and then lets me sort and filter later in a way that’s appropriate to that device.

Here’s a more advanced scenario to illustrate how it might work:

- In a tweet someone mentions a video of a good conference talk. I add it to my “later feed.” In my car, I open my music player which can see my feed. I filter for videos and select the option to play it back with audio only.

This sort of thing isn’t hard, but it should be much much easier. Plenty of smart people are thinking about this. So tell me: what’s the right vocabulary here? General Systems Theory people call these stocks and flows of information. They’re related to Twitter feeds, Google+ Circle streams and Facebook activity feeds. Until someone tells me the canonical nomenclature, I’m going to refer to it as Latering cool stuff to my Universal Later Feed.